| History of the Burmese Cat |

|

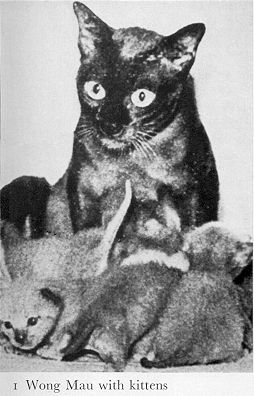

The Burmese story began in America in 1930 when Wong Mau, a shorthaired brown female cat, was brought from Burma to San Fransisco by Dr. Joseph Thompson, he was a retired ship’s doctor of the U’S Navy. He obtained Wong Mau from Frank Buck, a renowned collector of wild animals. Wong Mau had a special place in Dr Thompson’s affections and she became a familiar sight at his consultations.

Hoping to shed some light on Wong Mau’s genetic make-up, Dr. Thompson asked three of his breeder and geneticist friends (Virginia Cobb, Clyde Keeler and Madeleine Dmytryk) to co-operate with him in a series of breeding experiments. As there was no other cat of the same breed with which to mate her, Wong Mau’s first husband was a Siamese, Thai. Two types of kittens resulted. One was typically Siamese the other identical to Wong Mau, with her dark coat and darker points. When one of the latter was mated back to Wong Mau three types of kittens were born – some Siamese, some brown with points and some solid brown with little or no darkening of ears, tail, feet or mask. When these solid brown kittens were mated together, only solid brown kittens were produced. The detective work of Dr Thompson and his colleagues had paid off. They had proved that the Burmese was a distinct breed with a sound genetic basis. Despite the fact that Dr Thompson and his colleagues had proved that the Burmese belonged to a newly-discovered true breeding variety, the way to its recognition and development in the US was not an easy one. The breed was first recognised by the American Cat Fanciers’ Association (CFA) in 1936 and in the decade that followed Burmese began to achieve major successes at shows. Then however came a harsh setback as the CFA suspended its recognition. Many years later, we can only speculate why it happened, but at the root of the problem seems to have been the small number of purebred cats available and the necessity of outcrossing them with Siamese. From articles which appeared in magazines at the time, it appeared, too, that some breeders had difficulty in distinguishing between pure Burmese and Burmese/Siamese hybrids and that a few others deliberately exploited this confusion by producing hybrids and passing them off as wholly Burmese. Fortunately in the long run this seemingly devasting setback did little but good for the breed, for it made responsible breeders even more determined to extend and improve their stock. Finally in 1953 the CFA was sufficiently reassured by the development of the breed to restore its recognition. All

Burmese that were born then were always brown/sable and had always

been without any barring (no ticked no tabby). That was then already

a very important issue. It seems, that the cats like Wong Mau were known in Britain as long ago as 1889. But with their dark coats at the time less fashionable than the more immediately striking colour of the Royal-Cat-of-Siam, they were passed over and we do owe it to Dr. Thompson and the other dedicated American breeders that the unique Burmese is delighting us today. The British development of the Burmese did not begin till more than half a century later. For that we must be grateful to Mr & Mrs France of Derby. Still Mrs France was forced to give up her Burmese and therefore Casa Gatos Darkee, an American Burmese stud, who came to England in 1953, was handed over to Mrs C.F. Watson who carried on breeding. Darkee mated her queen Chinki Yong Yetta, the mating that would eventually produce the first blue Burmese. By 1956 it was safe to say that the Burmese had truly arrived. The Burmese Cat Club had been inaugurated with more than 50 founder members, many well-known breeders were starting lines of their own. British Burmese were exported to Kenya, New Zealand, Ceylon, Canada, Ireland, Scandinavia, Australia and South Africa. In 1955 though began the story of the blue Burmese. That mating, previsously mentioned between Casa Gatos Darkee and Chinki Yong Yetta produced a female named Chinki Golden Gray. In due course Gay was mated back to her father, Darkee and presented her owner Mrs Watson with a litter of six kittens. In Leicester Mrs Smith’s Chinki Yong Kassa was also on the production line. Kassa though produced only a single kitten but she was a confident, experienced mother whereas Gay was a young cat coping with her first litter. Their two owners, close friends, decided to alter slightly the sizes of the family units. Two of Gay’s large family went to the motherly Kassa, who immediately accepted them and brought them up. It was a big surprise – Gay’s two kittens, a male and female, had been the same colour at birth but as the girl grew her coat began to lighten till at four weeks it was a light silvery grey. In 1955 when knowledge of genetics was not as widespread as it is now, this little kitten’s pale blue coat must have come as a disturbing puzzle to breeders engaged in producing a line of brown cats who were supposed to be breeding true. Now we know that there is a simple explanation. As previously explained, it was necessary to use Siamese in the early days of building Burmese stock. Possibly unknown to breeders at that time, some of the Siamese used for the purpose carried the blue (diluted brown) gene. If so, that blue gene might well have been passed to the Burmese/Siamese hybrid and then to a pure Burmese. All it needed was a mating between two sable Burmese carrying this respective blue factor. – This blue kitten was called Sealcoat Blue Surprise. She was a beautiful cat with a lovely disposition. She died in 1971. By 1960 they were recognized by the GCCF with championship status. With the arrival of the blue Burmese breeders became interested in the possibility of yet more colour variations. Around 1959 in America, some paler-coated brown cat had been observed in litters. They were apparently cats in which the normal brown gene of the Burmese (genetically black) had been replaced by a genetic brown which appeared as a milky chocolate colour. It occurred to breeders that these light cats were akin to chocolate-pointed Siamese, and if this was so, a blue-diluted version could be obtained. This did in fact turn out to be true. In America these light browns became known as champagnes and their blue-diluted counterparts as platinum’s. In Britain they are called chocolates and lilacs. In 1964 came the introduction of even newer colours in Britain, namely the reds, creams and torties. The production of these colours began by accident, when a blue Burmese female escaped and eloped with a short-haired red. Breeder’s curiosity was sufficiently aroused for a breeding programme to be undertaken. From this first accidental mating of the blue and the red was a very elegant black and red tortie of foreign type. Meanwhile, a brown Burmese female had been deliberately mated to a red-point Siamese, and a tortie Burmese/Siamese hybrid from this alliance was used for further breeding. A third line was established when a tortie moggy (carryng Siamese) was mated to a brown Burmese carrying blue and a male kitten was kept. Despite the hard work, expense and occasional misfortune (one litter was lost with cat flu when three weeks old) breeders triumphed eventually in getting red, cream and tortie cat identical in personality and appearance to the more traditionals brown – typical Burmese. By 1973 the creams had championship status and last of all the torties were given it in 1977. |

|

Text/Translation

©

copyright by: Irmgard Thormann, Mackintosh Burmese Cats |

|

|

In

those days, Siamese had shorter heads and a slight nosebreak, rather

than the triangular shape and straight profile which is required today;

neither did they have such a distinctive whip tail. American cat fanciers

of the day took Wong Mau to be nothing more remarkable than an unusually

dark-coated Siamese. Thompson however having compared her with his

Siamese, realised that there were some marked differences in type.

A small, fine boned cat, Wong Mau was rather more compact in body

with a shorter tail, rounded widely.spaced eyes and a domed short

muzzled head without any sign of a pinch. Reports vary as to her eye-colour

– some say golden, other turquoise – but all agreed on

the darkness of her points compared to her body colour, indicating

that Wong Mau was in fact a Burmese-Siamese hybrid.

In

those days, Siamese had shorter heads and a slight nosebreak, rather

than the triangular shape and straight profile which is required today;

neither did they have such a distinctive whip tail. American cat fanciers

of the day took Wong Mau to be nothing more remarkable than an unusually

dark-coated Siamese. Thompson however having compared her with his

Siamese, realised that there were some marked differences in type.

A small, fine boned cat, Wong Mau was rather more compact in body

with a shorter tail, rounded widely.spaced eyes and a domed short

muzzled head without any sign of a pinch. Reports vary as to her eye-colour

– some say golden, other turquoise – but all agreed on

the darkness of her points compared to her body colour, indicating

that Wong Mau was in fact a Burmese-Siamese hybrid.